Grief Makes Ghosts: Hauntology and The Last of Us Part II

A very long close-reading of a ghost story

Nearly four years after its launch, The Last of Us Part II still haunts the gaming landscape and has lodged itself in many gamers’ memories. The original game, The Last of Us Part I, ends with a moral dilemma I’ll probably never stop thinking about. The Last of Us Part II is arguably just as impressive in crafting a narrative that sticks with people. But the sequel was far more divisive than the first, for many reasons—none larger than the haunting ending that divides opinions as much as anything else in the recent years of explosive growth in gaming.

Spoilers ahead. You probably won't understand the text here if you haven't played and finished both parts of The Last of Us. I do my best to summarize the narrative, but the games’ collective story is dense. This essay is geared toward people who have played the games, so you should do yourself a favor and play them both. Or at least watch playthroughs on YouTube.

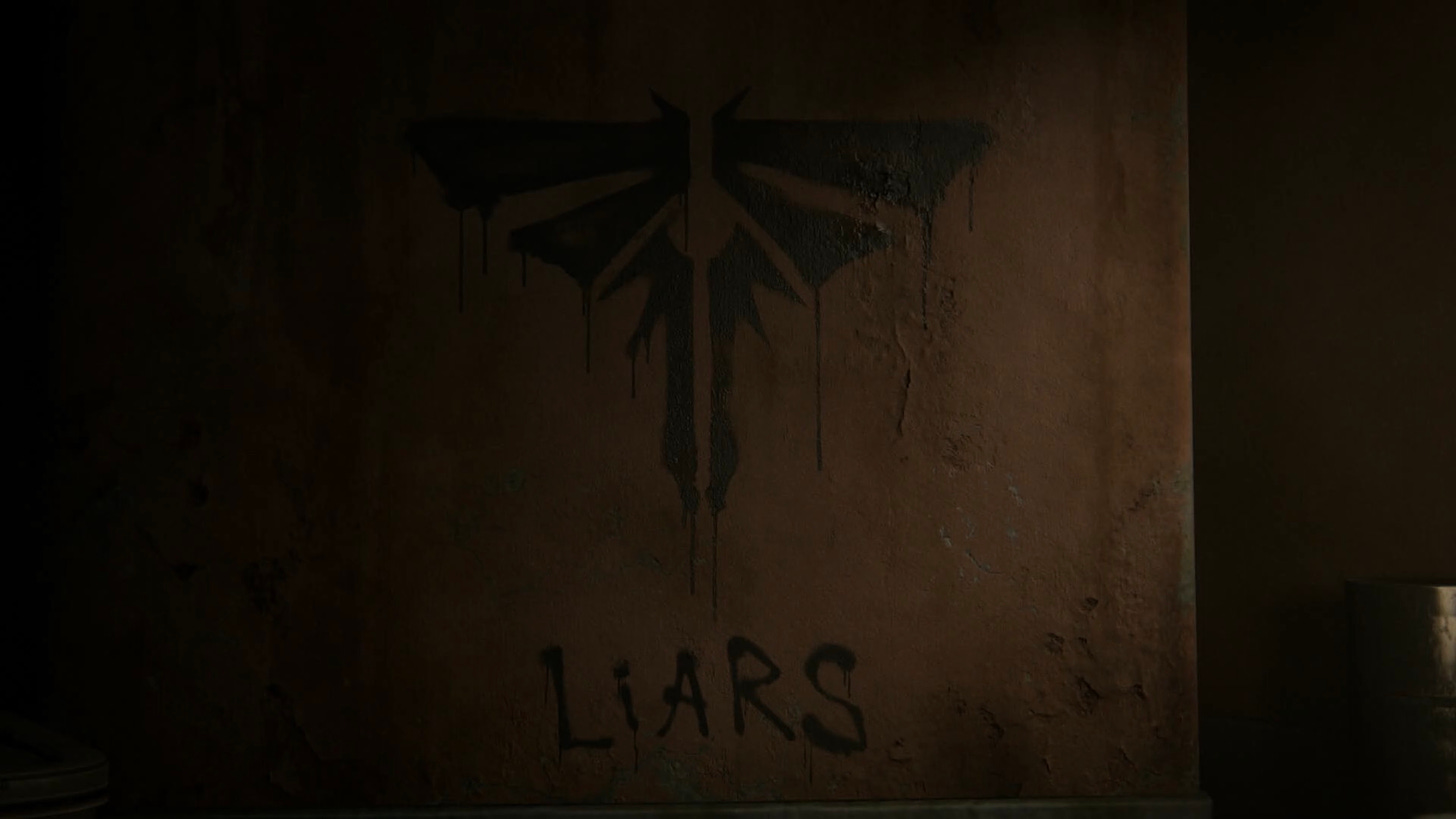

People talk about Ellie’s choice at the end of part two in very reductive, black-and-white ways. Though the game series is anything but black and white, people treat the end of this game as essentially just a trolley problem to be solved (many treat the dilemma of the first game’s ending like this too, but far less often). Though people have analyzed this game from many different perspectives, I'm here to give one I haven’t seen: a hauntologically informed close reading of the game’s narrative. Hauntology (haunt and ontology = hauntology), for my purposes here, offers a set of perspectives that coalesce around a foundational notion that things of the past, whether of cultural or personal importance, return or echo onward in the present time, coming back to us like (metaphorical) ghosts and causing temporal dissonance in our perceptions. Our minds flashback and/or insert aspects of the past into the present, often the aspects we aren’t emotionally able to leave behind when we’re traumatized, and this experience is like being haunted. The temporal dissonance of haunting is prompted by physical sensations, objects, places, or people that connect us via memory to the past. This is what people are getting at when calling a place a “haunt”—it is a place where time is disjointed because it suggests so many memories. One proponent of hauntology, noted critic Mark Fisher, claimed that cultural objects like songs or films come back “‘on YouTube or as a box set retrospective’ like the looping, repetitive time of trauma" and that hauntological art deals with confronting "the failure of the future." I think objects of personal importance, mementos, and the like, as well as the living bodies that signify and hold onto the past, also tend to haunt us by triggering memories of trauma and in turn provoking experiences of grief; often these triggered memories are also at odds with the reality of the present and symbolize a hope for a future that never came to be. And this is what happens in the stories of TLOU.

The Last of Us Part II is one long ghost story—and so is the story of the first game, since the plots of both hinge on lost futures and painful pasts. Ellie’s controversial choice at the end of the second game is ultimately made because grief-stricken memories haunt her and her enemy Abby as they struggle to move forward fully into the present. A large part of why the lens of the ghost story best explains the game’s seemingly irrational ending is because ghosts themselves represent irrationality in humanity. In ghost stories, people do irrational things out of complex, overwhelming, and mishandled emotions. There aren’t literal ghosts in either game (though the recently released creators’ commentary in TLOU2’s remastered version revealed there was originally a ghost version of Joel that Ellie would somehow speak with, as hinted at in the game’s reveal trailer), but there are complex, overwhelming, and mishandled emotions. These emotions stem from being haunted by the ghosts that exist through grief and grief’s often attendant traumatic memories. My analysis here lays out the baffling logic behind the actions taken by Ellie and Abby to show that they are motivated to make peace with the ghosts of their pasts, even though ultimately their decisions cause more grief and trauma along the way.

A warning: this essay is very long (about 13k words). It’s a bit rhapsodic as I address many aspects of the game beyond just the narrative to bolster my argument that the ending, and therefore the whole game by extension, is best understood hauntologically. And yet there’s still enough I don’t mention to turn this into a book. I find that most essays online about this game are too short, with far less evidence than opinion (surprise, surprise). They insufficiently perform close readings of it as a text (there is a lot of content to manage), so my analysis strives to be granular and thorough, looking at everything that follows hauntological logic to explain the narrative choices, particularly through examining the trauma and grief of the main characters. I’m trying to not miss m(any) of the resonant details threaded in the easily 20-plus hours of gameplay because that is what many do. I get that a lot of people will be tempted to check out, but if you stick around, you might just appreciate the game even more—or for the first time. So grab a drink and get comfy.

Looking Further Than the Characters Do

Let’s first get into the debate over the ending, which doesn’t make as much sense as it could if you don’t look at the narrative as a ghost story. There are essentially two dominant, vocal camps online when it comes to interpreting the game’s final confrontation between Ellie and Abby, and neither incorporates ghosts in their analysis.

The first camp claims that, despite killing potentially dozens of people to get to her target, Ellie doesn't ultimately kill Abby because she realizes she would be perpetuating a “cycle of violence,” which writer/director Neil Druckmann famously said the game was about before it was released (it’s not only about that, of course, no matter what he or any of the game designers say). This is a cycle that Joel began by killing Abby’s father Jerry, who would’ve killed Ellie via brain surgery (without her expressed consent) so to make a cure for the Cordyceps infection that mutates people into monstrous beings, an infection to which Ellie is immune. First campers often argue that Ellie sees how Abby had taken a younger person under her wing, Lev, and that this dynamic reminds her of what Joel and she had before he was killed, so she spares her enemy, not wanting to put Lev through what she experienced when Abby brutally murdered Joel in front of her. Or they say that Ellie forgives Abby so she can in turn forgive Joel for preventing Jerry and the survivor group the Fireflies from using her brain to make a cure and then lying to her about it (though it is unclear if she’d have chosen to do it, at 14, if she wasn’t unconscious when the Fireflies found her). Or they use some other reasoning that argues Ellie didn’t want to kill Abby because she’d simply had enough of violence and decided to focus on forgiveness. These sentiments, in my view, only partially explain Ellie’s choice. Ellie didn’t want to commit violence and it wasn’t the goal of her revenge (she’s not a psychopath, evinced by her relationships, especially with her adopted son later on); instead, she would only commit violence as a means to an end. I'll get to what that end was. But the violence itself wasn’t what motivated her at her deepest core—it was only the consequence of what motivated her.

The second, more utilitarian-minded camp says that all the people Ellie kills to get to Abby are for nothing if she doesn't kill Joel’s murderer. And since she chooses not to, the game therefore is bad. Or narratively bankrupt. Or simply a mess. But nearly all of the people who think the game's story isn't good essentially can't fathom Ellie not killing Abby after the arduous, killing spree of a journey she takes to find her. It simply doesn’t compute to the second campers. And this is understandable if one doesn’t examine the characters’ (or their own) grief-stricken emotions further than Abby or Ellie do themselves for the majority of the game. But we can look further than that.

We can look further than the notion that Ellie would be motivated by an abstract idea like “ending a cycle of violence,” too. In a horrific world like hers, where her walled town of Jackson is barely able to keep civilization alive, what she is motivated by most is her long-term emotional well-being, as most people would be. With only Joel, his brother Tommy, and Tommy’s wife Maria knowing she’s immune, Ellie is particularly isolated while she goes through a maturation period at 19 years old, a time that centers on carving out an identity. This makes her motivation for well-being all the more urgent.

Yes, Ellie wants to happily live with her girlfriend Dina (and later Dina’s son JJ), but she still pursues Abby relentlessly, even after ceasing for a long time. Why? Because Ellie feels she cannot be well in an already monstrous world where Joel is remembered as an evil monster.

Ellie holds on to a view that there is good in the world, and that Joel was part of the good as well as the bad, just like her. She implicitly knows she will be haunted by his past actions forever, so she cannot allow this haunting to be wholly negative or she will lose herself to nothing but pure, Darwinian-minded survival. Before Abby came along, her view of Joel’s impact on her life was already getting increasingly negative, after she’d discovered evidence of the truth of what happened in the Firefly hospital. Joel’s lie was that there was never a chance at a cure and there were dozens immune like her, which surely made her feel less special and more isolated simultaneously. Once Abby did come along, she’d just started to balance out that negativity by wanting to forgive Joel, even though she doubted she could. Before Abby found Joel, Ellie had only recently started to accept that Joel’s decisions were always going to affect who she was and what she wanted to do with her future. She was starting to mature into an adult. Then Joel was murdered and Ellie’s past was thrown into question again, rupturing her burgeoning identity as well as a recently gained foundation for her peace of mind—the truth of what Joel did to save her life.

A cycle of violence may end, even in the desolate world where Ellie and Abby live, but only if one accepts they might be haunted forever by the ghosts of people that drove them to or were involved in an act of violence in the first place. Grief makes ghosts of our memories of the dead. Trauma stored in the brain makes us want to control these feelings of grief. And then ghosts spark our trauma responses.

What we do with our haunting memories, how we decide to exist in the present when the objects of the world around us are reminders of what we want to forget, determines if we will heal or continue to harm. But often, if we are traumatized deeply enough, our actions are irrational and somewhat at odds with our best interests.

Ellie Acts Like Joel to Redeem Him

Ellie’s choice not to kill Abby hinges on the moment Ellie has a flashback of a conversation with Joel, which the player only sees in full after Abby escapes. As Ellie holds Abby’s head underwater, the camera zooms in closer on her face before a flash of Joel playing his guitar on his porch appears, followed by Ellie’s forlorn face again—and then she lets Abby come up for air. Just before this, Ellie had had half of her ring and pinky fingers on her left hand bitten off by Abby—fingers that she used to fret the strings of the guitar Joel gave her. Realizing she’s lost a sensory connection to Joel due to needing her fingers to play guitar, the same fingers that were choking Abby’s throat, Ellie lets go. Arguably, it was the haunting loss of her fingers that emotionally (and possibly literally) kept her from properly choking Abby. As Abby regains her breath, Ellie tells her “Go. Just take him.” This bit of dialogue could refer to the unconscious Lev, Abby’s companion who she has laid in a boat for their escape, but as many have pointed out, it can refer to both Lev and Joel. This is because Ellie, despite not wanting to believe it is true until this moment, knows deep down that leaving Abby alive keeps the good and merciful side of Joel alive, including in herself. As painful as it is for Ellie to let Abby go, the ghost of a good Joel will more likely live on for future generations if Abby lives on at her mercy.

Ellie finally admits to herself, after already killing relatively innocent people like Abby’s friends, whose deaths already couldn’t alter her subjective experience of Joel’s ghost, that this ultimately paradoxical decision is what she wanted all along. This is true on its face for a couple of interdependent reasons. First, since Abby purposely sought to take Joel’s life (he wasn’t a faceless casualty of a battle—she told him he “didn't get to rush” his death), Ellie knows Abby carries the memory of that taken life onward, even if the memory is negatively viewed; second, because Abby carries this memory, she could become haunted by Ellie and therefore Joel by proxy, so that Ellie’s mercy, not violence, also keeps Joel’s ghost echoing into the present and affecting the world with more (even if diminishingly loud) chances to resound in positive ways, such as Abby protecting Lev or even Abby finding a way to help make a cure happen.

By letting her live, Ellie makes Abby’s life defined by Joel’s good in addition to his evil. Anytime she remembers the friends Ellie killed, she might think of Joel and Ellie. Anytime she thinks of the Fireflies, especially, she might think of Joel and Ellie. These are negatively skewed reminders. But by letting her live, any time she looks at Lev, Abby will know that Ellie let them both go. And she will have to wonder why. Abby will have to square her life and anything she does for Lev’s sake with Ellie killing all her friends, but not her. And squaring that involves remembering Joel, even trying to understand him. Abby herself has already been haunted by her father and his ambition to make a cure, but after her second and final confrontation with Ellie, she will be haunted by Ellie and Joel too—specifically by the way Ellie and Joel saw each other.

Because Ellie can't let Joel’s memory be forever distorted in her mind, since this was driving her more than her relationship with Dina and her adopted son JJ, she was never going to kill Abby. This would confirm that Abby was right about Joel and, in effect, her too. She may have told herself she would kill her for most of the story, if only to justify killing Abby’s friends to get to her, but she never wanted to kill her the way Abby wanted to kill Joel. This might sound crazy to you if you’ve played the game. But remember that when most of Abby’s friends want to kill Ellie in addition to Joel so to not “leave loose ends,” Abby decides to let Ellie live. Ellie is only alive at Abby’s mercy. She may have said “I’ll fucking kill you” in the moment after Abby finished murdering Joel, but this was before Abby stopped everyone in her group except her ex-boyfriend Owen from killing Ellie. After recalling this moment, Ellie could feasibly deduce that Abby let her live only to remember the bloody, brutalized image of Joel’s body as proof that he was a monster. Based on the actions she takes to not kill Abby, Ellie ultimately wants to give herself evidence to remember Joel as good—and not worthy of the death he received. To ensure this is her memory, she goes after Abby to change her enemy’s view of him as her own proof he isn’t a monster. Ellie wants Abby to question her actions and, in turn, be haunted by her and Joel’s ghosts. Abby can’t be haunted if she is dead, and killing her would only be proof to Ellie that Joel was bad.

The difference in the form of retribution between these two is that Abby had not been betrayed by her father as Ellie had by Joel. Because of this, Abby is relatively clear-minded about wanting to take an eye for an eye. Before killing him, Joel doesn’t haunt her because she’s never interacted with him; he’s only an obstacle in the way of putting her father’s ghost to rest. She thinks killing Joel will put Jerry’s ghost to rest because she is haunted by the good her father wanted to do, not the bad he factually did. Killing Joel would be to erase the reminder of what took away this possible future good. The abstract nature of the good left undone prevents Jerry’s ghost from as presently haunting the world as Joel’s would, since, according to hauntological logic, evidence of Jerry’s undone intentions is practically nowhere to be found in concrete terms—except: 1) in the memories of Fireflies who remember him, Abby’s “Salt Lake Crew” who joined with her in the Washington Liberation Front (WLF), (but notably all are too young in the game’s timeline to know what the world could’ve been if it ever again looked like it had pre-apocalypse via the vaccine), and 2) in the existence of Joel, who represents the death of Jerry’s vaccine-filled future. So, for Abby, killing Joel equals forgetting about Jerry’s unseen future and burying the remnant of it which could’ve represented its heroic beginnings rather than its tragic end. Ellie’s entire existence, on the other hand, is defined by Joel killing most of the Fireflies at the Salt Lake hospital and taking Ellie away after they traveled across the country for nearly a year to get there. She literally cannot get away from Joel’s ghost because she would not exist without his violent actions—every concrete thing Ellie does, every breath, is haunted by Joel’s deeds. Plus, having no family, she lives near him and his brother afterward. This burden complicates her sense of agency, especially when vying for revenge against Abby. Her ability to choose who she wants to be is further complicated in part two because she would not exist if it weren’t for the mercy of the person who kills Joel. In my view, Abby only lets Ellie live because she believes this will help put her father’s ghost to rest. Ellie suffering because of her supposedly righteous revenge is, for Abby, more evidence that Jerry’s goodness was truly taken from the world by Joel, whose actions have only caused a chain reaction of suffering. Abby is reenacting her trauma to gain a sense of control over it, but this doesn’t work, which I’ll speak more about below.

Because Ellie becomes as defined by Joel’s violence as she has his goodness, she desperately wants to obtain her own identity amid her trauma. Having been forced to be haunted by a distorted, monstrous view of her loved one, Ellie seeks to emotionally exorcise Joel’s ghost and gain a sense of agency. The problem is she can’t do this if Joel is seen, particularly by herself, as a monster incapable of good because it follows that she, a person he loved and killed dozens for, is also incapable of good.

To have direct access to Joel’s ghost before she journeys to Seattle to find Abby, Ellie stops by his house to pick up a few of his things. There are many flowers outside the house, indicating how positively he was viewed by the town of Jackson, the town that didn’t know what he’d done to the Fireflies and which couldn’t truly prove to Ellie Joel was good. First, she finds the jacket he died in and smells it, a typical way the aggrieved use a concrete sensation to access memories, and sees a few other mementos that remind her of their past together. Then she finds his shattered watch and revolver in a box. The watch, which Joel’s daughter gave him and was broken when she was killed, represented only Joel’s experience of temporal dissonance at first—until Ellie inherits it as a memento of her own haunting grief. The revolver, on the other hand, is a tool that represents the lengths Joel would go to for his loved ones, even if he had to commit dark deeds.

But though Ellie is haunted by some evidence of an evil Joel, she never actively tries to kill any of Abby’s friends in her course of revenge, despite their part in Joel’s murder. She almost always gives them a chance to live by giving her what she wants: Abby’s location. This is in opposition to Joel's brother Tommy, who at one point indiscriminately fires his rifle from a sniper’s nest at Abby and Manny. All members of the Salt Lake Crew—Nick, Jordan, Leah, Nora, Manny, Owen, Mel—were either killed by someone else (Tommy killed Manny and Nick, Leah was killed by the WLF’s rival group the Seraphites) or Ellie gave them a chance to live if they’d only agree to give up Abby (the exception is Jordan, who captured Ellie; she was forced to kill him to protect Dina). Ellie didn’t want or need to kill them for the sake of Joel’s memory, but she would, if necessary, to ensure that his goodness would haunt Abby.

Ellie’s goal is to prove to Abby how good Joel was to her, so again, if she tries to prove this by killing her, or kills her after proving this, she would only appear as evil as Abby thought Joel was. However, because her identity is so defined by Joel’s life, Ellie is prone to pursuing her goal by whatever means necessary, as Joel taught her by example in their journeys together (when Tommy and Ellie debate tracking Abby down, she tells him Joel “would’ve been halfway to Seattle already”). Ultimately, Ellie desperately needs his memory to be at least partly good in the mind of the person who thinks he’s purely evil. This would be proof to Ellie that she wasn’t just abused or manipulated into loving Joel. Ellie needs Joel’s memory to be a ghost she could live with, rather than live down.

Regardless of her goal, the fact is that Ellie does end up killing many people in the course of the story to demonstrate Joel’s goodness to Abby. At this point, one might ask: “Why would Ellie kill all the other people who helped Abby murder Joel, like Nora or even Mel? They could’ve been persuaded that Joel was good too.” The answer to this is that none of them were haunted by Joel’s actions enough to do what Abby did. None of them could see him as purely evil as Abby, who lost something more concrete in her father in addition to the idea of a better future her friends all lost. Joel tells Ellie in one flashback: “There was no cure.” As a concrete thing, he is right. It didn’t exist (at least yet), so this is somewhat true. The Fireflies were putting their faith in a doctor—a surgeon, actually, and not an infectious disease expert—to develop a vaccine, but there was no guarantee it would work, even if he killed Ellie to make it.

The other members of the Salt Lake Crew were former Fireflies who knew well what Joel did, but none had their emotional lives as directly and concretely broken by Joel as Abby had. Again, the tenuous future Jerry promised cannot haunt deeply without much evidence of its existence in the past that would remind others of what never came to be. When she’s killing Joel, Abby asks Owen: “You want what I want, right?” but he just tells her to hurry up and “End it.” He is telling her to let go of Jerry’s haunting power over her by getting rid of the only evidence that what might’ve been with a vaccine was taken away. Later, when Ellie finds Nora to ask where Abby is, Nora facetiously tells her she heard Joel’s screams every night, only to follow that up with “That little bitch got what he deserved.” This implies she wasn’t truly as haunted by Jerry’s loss as Abby because a reassuring measure of justice has been served. It is noteworthy that when Nora learns who Ellie is—the immune girl—just before she is killed, she becomes more deeply haunted by Jerry’s loss, as Ellie’s concrete presence is more evidence of a negation of Jerry’s unseen future. And so Nora begs her to think of all the infected people who are dead because of Joel’s decision, to persuade her, possibly, to stay alive until a cure can happen. Nora begins feeling haunted by Joel all over again here, all while she is breathing Cordyceps spores because Ellie was forced to tackle her down into an infected part of the hospital they’re in to escape other WLF soldiers. She would be dead soon at this point, and so even if she could’ve possibly been a smaller part of carrying on Joel’s memory positively, it was too late. At this point, Nora becomes merely an obstacle in Ellie’s mission to make her memory of Joel good again. Despite the additional trauma Ellie experiences after torturing Nora to get Abby’s location before killing her, in her mind she only does this to remove the obstacle for the greater good—just as Joel would’ve.

Ellie confesses what she did to Dina afterward, then tells her she doesn’t want to lose her. She is probing for whether Dina sees her as a monster now. Dina simply tells her “Good” and hugs her, tacitly allowing Ellie to feel justified and not feel more evil, less herself. They both know she needs this to survive in their situation, as her trauma could cause her to fully break down at any moment.

If you have PTSD, as I'd argue Ellie, Joel, and Abby do, you will sometimes attempt to reenact the thing that haunts you the most. (I speak in part from my own experience with PTSD here). Joel reenacted his loss of Sarah to a callous US military by killing the Fireflies; Abby reenacted her loss of her father by killing Joel. Though I disagree with the writer’s notion that Ellie thought killing Abby was the only way to make the violence in Seattle mean something (because of the pains she took to not kill), this article at Sofie’s Take persuasively makes the case clearly that Ellie, at least, suffers from PTSD. But there is a key comment that the writer makes about Ellie that applies to the other characters I mentioned (and arguably nearly all the survivors in the game-world):

[R]eenacting trauma isn’t a fully conscious, voluntary activity. It’s as if your own body and mind are hiding things from you. The way a survivor copes with the overwhelming negative emotions and feelings can often be misguided and destructive. Afterwards, the survivor not only has to deal with the consequences of the original trauma, but also with the feelings of guilt and regret, as well as the eroded image of herself.

In addition to PTSD from Joel’s death, it is easy to argue that Ellie has survivor’s guilt from her experiences of the first game, in which many people died around her in her journey to make her immunity matter to the rest of the world. This trauma and loss of self-worth is already haunting enough, though until Joel dies it might have been buried and not very present, as Joel consistently tells Ellie in the first game to not talk about the people they lose in their journey. Once she loses Joel, whom she’d told is the “only person who never left her,” it is reasonable that her focus on redeeming his memory is reinforced by her desire to not dredge up her previous trauma, as she might’ve come to see his policy of not talking about people one has lost would’ve been largely selfish and harmful to Ellie’s long term well-being.

For Ellie’s eroding image of herself to stabilize she must secure a legacy for Joel that includes more than just mirroring the negative consequences of her loved one’s actions. She does this mirroring through the killing she does to get to Abby. Ultimately, she is only successful at redeeming his memory when she does something good—merciful—by rescuing Abby and her sort of adopted sibling Lev from slow, agonizing deaths. She is successful because, although it seems like her entire journey was meant to end another way, like Joel’s in part one, she ensures that the goodness she feels she learned from Joel impacts Abby as much as his darkness has. But Ellie has been so deeply affected by both aspects of Joel herself that her trauma responses ensure Abby is first harmed before she is helped.

Abby Acts Like Her Father to Redeem Herself

Of course, Ellie could not make Abby view Joel positively if she wasn’t ready to see people in morally gray terms.

Abby is haunted by the loss of her father and the hope for a better future that his vaccine represents. She seeks Joel as a way to reenact her trauma and gain some control over it, just as Ellie does in seeking her out. But until Abby tries to be like her father, she isn’t successful at gaining peace with his death.

There are flashbacks in her storyline as well as in Ellie’s. In the earliest one, we see Abby as a young teen about the same age as Ellie in the first game; she finds her father on a mission to help a zebra who was caught up in barbed wire, despite the area being dangerous. In another flashback just after the zebra one, she learns what will happen to Ellie and tells her conflicted father that, if it was her that needed her brain removed, she’d want him to do the surgery. Though maybe she was naïve as a young teen, she believed in her father’s ability to do good even to the point of consenting, at least in the abstract, to the surgery that Ellie didn’t get to consent to.

Abby also has a flashback where she remembers finding her father’s dead body, and where she breaks down right away while her then-boyfriend Owen holds her. She is haunted by his death and she becomes a cynical person in subsequent flashbacks, unable to handle the loss of the future he represented. It is noteworthy that Abby doesn’t search for Ellie, but just Joel, because this indicates she was so ill-equipped to handle the loss of her father and his vaccine-future that she believes an immune person would only ever matter if her father existed to be the one to create a cure.

For a long time, Abby thinks simple revenge will quell her haunting. She begins to think in black and white, more so than most average teenagers do. In another flashback, when she was still with Owen, she shuts him down when he says the Seraphites might not all be terrorist-cultists. Her muscular physique, too, is a product of her black-and-white thinking: to get revenge and control the impact her trauma has on her, she must be able to control her body and shape herself into a highly fit specimen. But though Abby murders Joel, she slowly learns in the game’s present timeline that she couldn’t kill his ghost so easily. As long as there are living people who were impacted by Joel, like Ellie and herself, his ghost would live on through the objects, places, and, especially, minds that he made his memorable marks on.

Abby finds that the more she tries to get away from Joel after killing him, the more her past comes back to haunt her. Ellie and Tommy pursue her in retaliation. They do kill her friends, the last of the Fireflies she knew, and in return she kills one of their friends: Jesse (who is JJ’s father). Abby won’t be able to forget these things. Though it isn’t shown, it’s reasonable to assume she’d be guilty about killing Jesse, who she wasn’t sure had done wrong (and possibly Tommy, who she doesn't know survives her gunshot to the head). It's a safer assumption that she’d remember she’d only gotten to kill Joel because he and Tommy rescued her from an infected swarm right before. But the safest assumption? That she’d remember the painful effort Ellie went through to get to her.

All through the story, Jerry’s ghost doesn’t go away. After she kills Joel, Abby doesn’t think of him or Ellie and Tommy (until they attack her) but she does continue to be reminded of her father. This urges her to bring about a better, less destructive future, as Jerry wanted. She sets the broken arm of a Seraphite, Yara, who saves Abby from being killed by her own group. She dreams of Yara and her brother Lev being hung in the same room as her father was killed. Even though Mel labeled her the WLF leader’s top killer of Seraphites, she begins to question the WLF’s war with the group, haunted by the fallout of murdering Joel that causes her friends’ deaths by Ellie’s group, including her witnessing Manny getting shot in the head by Tommy. But besides Joel and Jesse, Abby mostly only kills Seraphites in the story. Early on, she surely tells herself the deaths are justified because of the ongoing conflict, like a good soldier, especially since she’s called their number one killer by the WLF leader Issac. Once she is helping Lev and Yara, she can justify killing them as rescuing her friends from a cult. When she kills members of the WLF, it is mostly in self-defense, as she has been labeled a turncoat. Though she struggles to be a turncoat, nearly leaving the outcast Seraphites Lev and Yara behind, ultimately she returns to them, hoping to help them escape their groups’ conflict with Owen and Mel at first, and later just on with Lev after Ellie kills these last two of Abby’s Salt Lake Crew and Yara is also killed. Abby becomes less driven by violence and revenge as she bonds with Yara and especially Lev, but when she finds the bodies of her ex-boyfriend Owen (whom she’d recently had sex with) and his pregnant girlfriend (along with proof of the killer's location), her better future free of the WLF with her friends gets taken away—just as her father and the better future he could’ve brought was taken away. She is retraumatized, haunted by concrete negations (dead bodies) of a future she didn’t get to have. And so she goes to find those responsible for killing her friends, ready to reenact her trauma.

In her first confrontation with Ellie, in the Seattle area, after all her friends have died, Abby kills Jesse as he bursts through a door, no questions asked, and soon shoots to kill Tommy. And yet, after fighting, she lets Ellie (and the pregnant Dina) go—but only at the behest of Lev, who’s just lost his sister Yara after she killed the WLF’s leader Issac to help Abby and him escape. Maybe Abby doesn’t want to kill anymore, but Joel’s past decisions continue to shape her future ones—until Lev gets her to be merciful again, to not kill a pregnant person the way Ellie / her group did (Abby doesn’t know Ellie didn’t realize Mel was pregnant until it was too late). But it is also clear Abby wants to be more like her father, and she listens to Lev because they’ve bonded deeply over prioritizing family above all else, as they’ve both lost a future due to the death of family members. Lev’s mother, a Seraphite who didn’t agree with Lev’s gender fluidity, accidentally dies when she hits her head while getting angry at her child for becoming an outcast due to his gender identity; even though Lev came to get her off the Seraphites’ island before the WLF attacked, she refuses her son’s offer of a future. When Yara dies minutes later to save her brother and Abby, Lev loses even more of what he thought his future was going to be like. Abby knows this pain. She tries to make Lev’s orphaning less painful by taking on a protective role, which she learned from her father. And so she has to be a good role model. Whereas originally Abby let Ellie live so that Ellie would remember how little Abby felt Joel’s life was worth to her, now she is trying to be more like her father. But though this alone is enough to keep Dina alive, the fact that Abby learns at the start of this confrontation that Ellie is who her father needed for the vaccine is part of what keeps her from killing Ellie too. She is trying to be more like her father, who was a person of hope and idealism about making a better world with a vaccine, so leaving Ellie alive—though she tells her she better not see her again—is a natural result.

But this isn’t the final confrontation. There is something of revenge still motivating Abby, whose closest friends are all dead. By warning Ellie to stay away, she is stipulating the conditions of her mercy and trying to stop seeking revenge. She wants Ellie to see her as a better person like her father, not the “piece of shit” that Mel told her she has always been, and not a person like Ellie, loved by a man who murdered dozens of people directly and maybe caused countless others’ deaths by needless infection. Abby sees things more morally gray than before the present-day events of the game that take place over three days in Seattle, but she is still haunted by a future where she was the daughter of someone who could’ve been the savior of the human race.

Over a year later, Abby, with Lev, is trying to find remnants of the Fireflies. She wants to revise her past and the tragic end of the Fireflies caused by Joel. She is trying to be at peace with her father’s ghost in this way. Her morals have become grayer, and so has her perspective on her future. She is hoping to find Fireflies Owen said he’d heard rumors of, and she has become idealistic to the point that she fails to abide by her military training, resulting in she and Lev getting captured by slavers who have either set a trap for people in a former Firefly outpost or listened to the radio signals coming from it to capture people there. Lev and Abby are captured in part because she’s still so haunted by her father and his unmade vaccine, despite killing Joel, despite proving to herself she is a better person than Ellie, that she lets her guard down after talking over a radio with a purported Firefly, hoping there’s a chance the group might truly still exist—that Joel, therefore, may not have fully destroyed the future she thought she’d once have. She has become the kind of person who might be convinced that Joel may not have been wholly evil. She has been highly idealistic, highly cynical, and then idealistic all over again. She has seen enough of humanity’s moral complexity—just as her father did, in his struggle to do the operation on Ellie—that she was getting close to putting her father’s ghost to rest.

Ellie Cannot Be Herself if She Thinks Joel Deserved to Die

Ellie doesn’t redeem Joel in her first confrontation with Abby, and so she continues to be haunted by his ghost, despite all her violent efforts.

Before the second confrontation at the end of the game, Ellie lives with Dina and her and Jesse’s son JJ (Jesse Joel—a haunting name if said, though no character does, because those people were both killed by Abby). They live in an almost idyllic farmhouse, away from reminders of Joel and Jesse back in Jackson. They are trying to accept that, because of Ellie’s actions, Abby’s friends are dead, Jesse is dead, and Tommy has been disabled by a shot to the knee—and possibly has had his brain damaged by a bullet too. Ellie has seemingly resolved to let Abby go, seeing that death and destruction are sure to follow if she continues to pursue her.

In this section of the game, Ellie experiences a PTSD-like flashback while in a barn with sheep. A shovel falls, making a metallic thud similar to the sound of Abby's golf club hitting Joel’s head and the haunting sets in full force: Ellie sees images of Joel being slaughtered by Abby and starts having a panic attack. She tries to fight it off, but when the barn door is shut by wind and there is no light, the scene switches to Ellie in a dark hallway from the beginning of the game that leads to the room Joel is murdered in. She hears Joel screaming her name and she tries to get in the room but can’t. To her, his ghost needs rescuing from those who, she presently knows, believed he deserved his punishing murder, the last impression Abby ensured he left on the world.

It is here we see her processing her trauma in earnest, rather than only reenacting it. Though the flashback is a little fictionalized and therefore reenacted in her mind, she is largely going through the facts, as painful as they are to remember. Until the barn flashback, it is reasonable to assume that Ellie has clung to the idea that she had eased her grief through some idea of retributive justice that takes the form of killing a bunch of Abby’s friends and ostensibly making her suffer this way (as Tommy seems to indicate would be enough vengeance against her before Abby confronts them in Seattle). But Ellie doesn’t feel completely better, over a year later. She still can’t let herself be at peace. She is still haunted. Here, Ellie becomes aware that she only ever wanted to find Abby to prove to her that Joel was good—and that she is good too.

Though Ellie is driven by negative, vengeful emotions for most of the story, in her grief she has been trying to make Joel’s ghost leave her in peace to do, and be, good. In the farmhouse, she dances goofily and flirts with Dina, plays with JJ, and even tells the baby she’d teach him guitar in the future, something Joel taught her. But to sustain this peaceful life and her well-being requires that she put Joel’s ghost to rest, too, by ensuring he is remembered fairly: as a human capable of both good and bad in a broken world. If Ellie doesn’t do this somehow, she cannot trust herself to keep JJ and Dina safe; during her flashback, JJ is crying, but Ellie doesn’t even hear him until Dina breaks her out of her panic attack.

Tommy comes by soon after her flashback, still driven by revenge against Abby, possibly due to his disability and separation from his wife (who didn't want him to go after Abby). He gives Abby's possible location to Ellie. Though she initially indicates she won’t go find her in Santa Barbara, to Tommy’s anger, Ellie later changes her mind. She gets up in the middle of the night and looks through her notebook of song lyrics and diary entries, which reveal how she keeps being reminded of Joel, of the good in him. There is also the subtext that Tommy, a living connection to Joel, is the person who knows best how Joel could be good and how he could be bad: they’d survived together and Tommy left him when Joel got too bad, as we learn in the first game. He was there when Sarah was murdered and watched it break Joel. And though it’s never shown, it’s obvious that Tommy would’ve had to tell Ellie that he and Joel saved Abby from the infected. He’s a reminder of Joel’s goodness himself, and he’s always wanted his brother to be at peace, even to the point that when Joel confesses to Tommy what he did to save Ellie at the very start of the game, Tommy tells him he doesn't know if he'd have done anything differently and promises to never tell another person about it. Tommy knows well the shades of who Joel really was and this only furthers her growing realization that what she wanted most was for Abby to see Joel the way she had, with both the good and the bad.

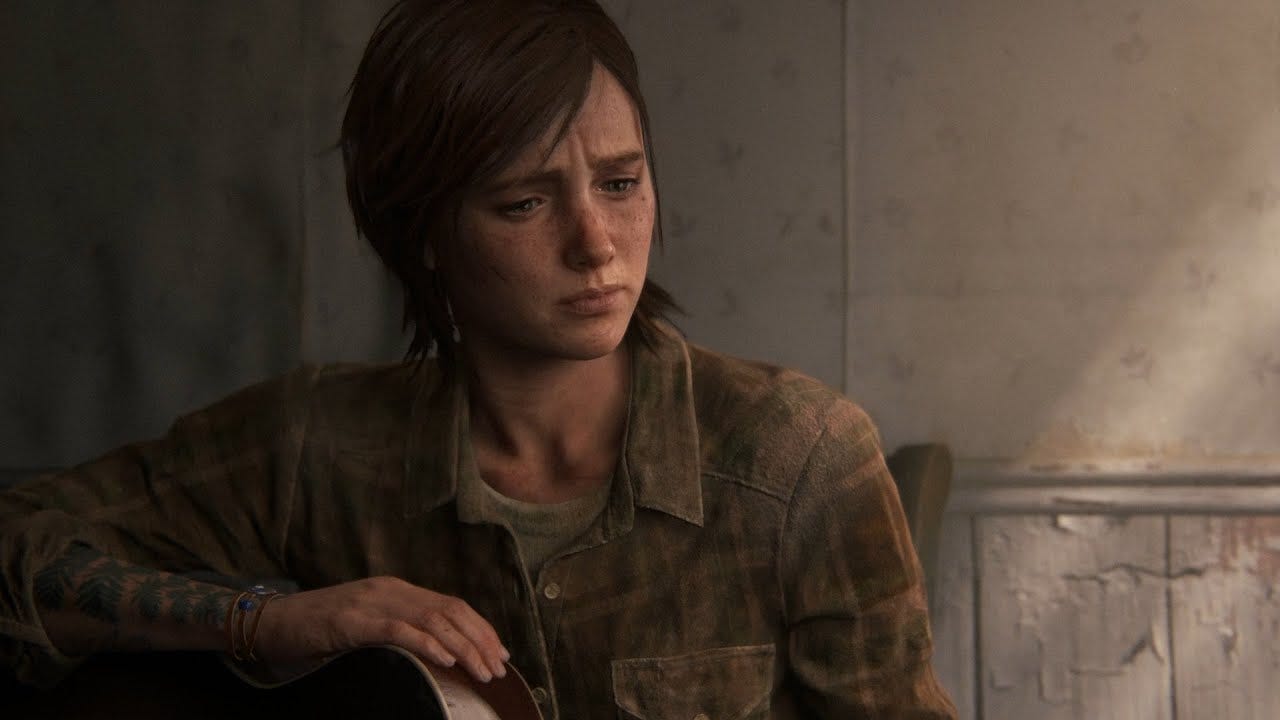

For this to happen, she needs to show Abby what his death had done to her—that it had only made her more like Joel, in both good and bad ways. When Ellie gets up in the middle of the night, she also plays the guitar Joel gave her—a haunting object of his affection and the guitar he used to sing a song for her, “Future Days,” when they’d first returned to Jackson from the Firefly hospital. The song starts “If I ever were to lose you / I would surely lose myself.” This is how Ellie feels about Joel, too—she plays the start of the song in Seattle while looking for Abby.

After playing the guitar Joel gave her again, she packs her bag to leave and puts on Joel’s old jacket, the one he died in—she is putting on his ghost, in a hauntological sense. She is still determined to stop herself from losing him—the good in him—by redeeming his memory for not just her, but also Tommy, Dina, and JJ. She knows she has already started losing the good in herself and she doesn’t know if there is a way to make Abby change her mind without violence, but she decides she has to go try. It is so important to her to change the memory of her dead loved one that she risks losing the ones still living by trying to sneak out without Dina knowing. Ellie gets caught, so she tells Dina she has to finish it. But she doesn’t tell her she has to kill Abby.

And she doesn’t. She rescues Abby from certain death instead, just as Joel rescued her, even if, for both of them, there was a different choice they could’ve taken, one that others told them was the better option.

As long as there is grief to be had about Joel, his ghost could be darkly encouraging Ellie to reenact his death to change the outcome and regain her sense of self as good, even if she rationally knows this will not work. The more people she killed, the more Ellie knew, consciously, that she didn’t want to kill Abby. The consequences of her trauma complicated her quest to redeem Joel and by extension herself. But seeing Tommy, an embodiment of some of these consequences, reaffirms her quest. As long as she has people she loves who also loved Joel, she’d be reminded of him. But her grief could be less triggering of her trauma if she could separate herself from Joel and put his ghost to rest. For Ellie to be self-determined, she’d have to tell Dina one day what Joel did to save her. But she doesn't want Dina to reject her because of this. So if Abby could believe Joel wasn’t completely evil, then it follows Dina wouldn’t dismiss both Ellie and Joel as monsters. Ellie says in the first game she is afraid of ending up alone, and the prospect of losing Tommy, and one day Dina and JJ, push her to find Abby again.

Trauma can cause people to cling to others, even if it is irrational to do so. Dina tells Ellie Abby doesn’t get to be more important than their family, but Ellie leaves to find her anyway. Though Joel caused them grief differently, Abby and Ellie find that they are ultimately united by reckoning with the trauma of having something profound taken away by him. They are, in effect, trauma-bonded—a connection that is ghostly in its imbalanced power dynamics, where a victimizer often holds more manipulative sway over the victim, even if they aren't presently there. By lying to get what he wanted, a replacement daughter who he’d saved from death and thereby reenacted his own trauma, Joel arguably victimized the younger, dependent Ellie (even if saving her itself was the right choice); but Abby also victimized Ellie by killing Joel in front of her and starting their cycle of violence. Abby has arguably been victimized herself, not so much by Joel, but by her own morally gray father—the zebra rescue scene demonstrates Jerry’s risk-taking tendency, to the point that he sometimes disregards his own and others’ safety for what he thinks is right. Abby’s deep faith in her father is something of an emotional necessity forced on her to cope with Jerry’s self-righteous behavior.

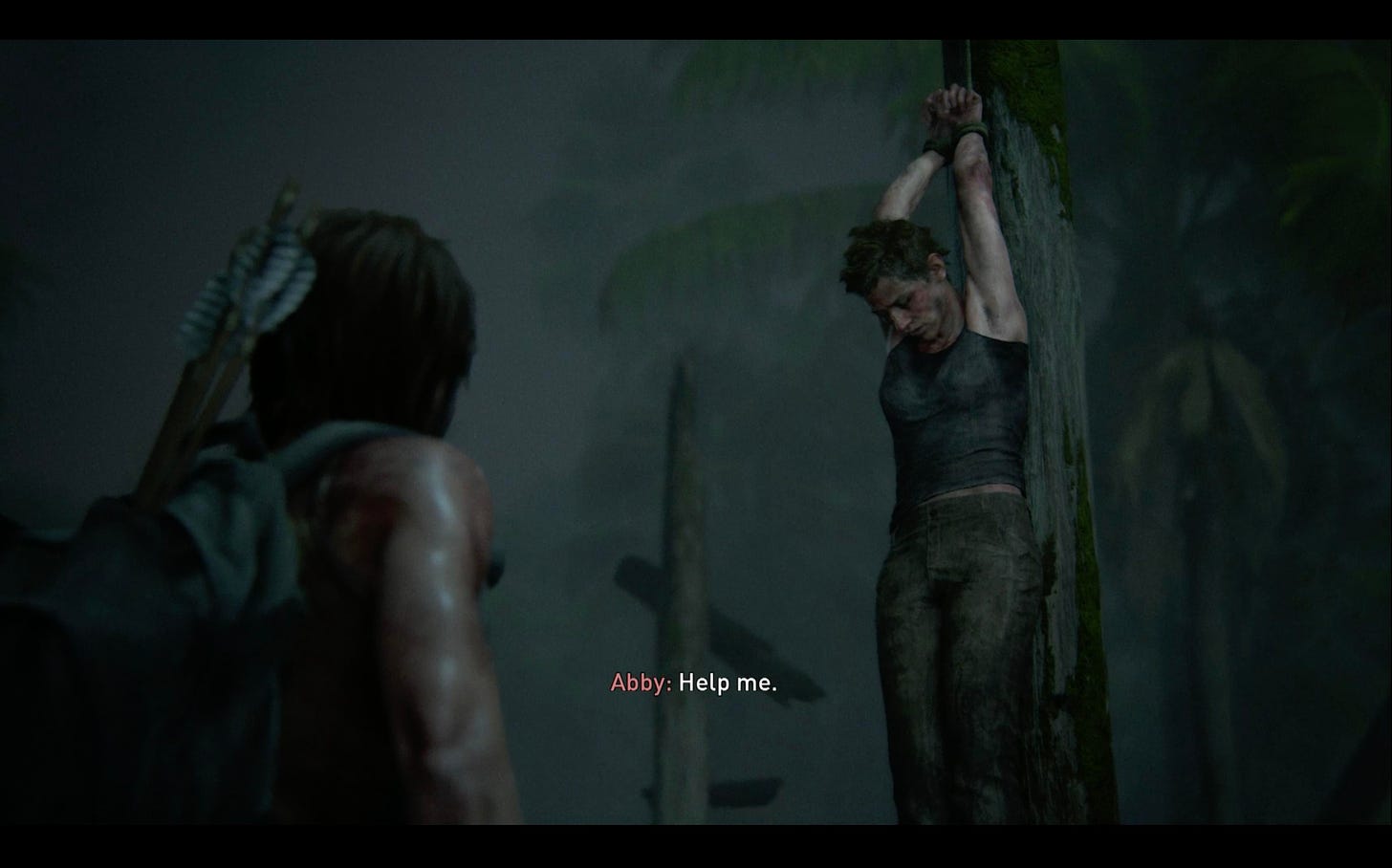

In their final confrontation, Ellie doesn’t simply kill an already emaciated Abby in her vulnerable state of hanging on a pillar (a hauntological symbol that shows how Abby's own self-righteousness, though eventually turned toward helping other slaves, has made her a pariah). She knows they are united by trauma—she even sounds concerned that Abby is dead when she calls out her name to find her among the other rebellious people strung up. Though they are enemies, they share a fraught kind of intimacy. Joel caused them grief differently, but Abby and Ellie are ultimately united by reckoning with the trauma of having something profound taken away by him. Abby is surprised but almost reassured when she sees Ellie has found her: “It’s you,” she says. When Abby cuts down Lev, she doesn’t hesitate long to turn her back on the switchblade-wielding Ellie. She trusts her to a degree. Once Lev is down, she tells Ellie there are boats by the water, putting out the possibility that they might even escape together.

Trauma-bonds, like the one Ellie had with Joel, can be as deep as any kind, and this connection only ends up motivating Ellie to change Abby’s mind about Joel all the more, even though she ultimately doesn’t know how to do this without also causing Abby physical pain, since trauma is their main form of communication. Ellie has a chance to let Abby and Lev go freely, and she even unloads her gear in her own boat. But she touches an injury she received from being caught in a trap by the slavers—a stab wound in the same area of abdomen Joel was injured in the first game—and then she has a flashback of Joel’s bloody, beaten-in head. Joel left the world in violence and so that's how his ghost often pops up in Ellie’s memory. She tells Abby: “I can’t let you leave.” When Abby, her back to Ellie, says “I’m not doing this,” Ellie grabs her and throws her into the water. Abby then tells her she won’t fight her and Ellie tells her she will, threatening Lev with her knife. Ellie takes this measure because, to her, Abby is explicitly rejecting her quest to redeem Joel’s memory by not continuing to build on the traumatic, haunting past they share. It is important to note that Ellie doesn’t attack Abby until she’s refused the traumatic terms of their bond, which Ellie then feels must be reenacted by both of them to make Abby change her mind about Joel. She has to win the fight, but she also has to leave some fight left in Abby for Joel’s memory to influence her positively. With the knife to Lev’s throat, Abby says he’s not “a part of this”—their trauma—to which Ellie replies “You made him a part of this.” And Abby, knowing this is true, has no other option but to agree to fight Ellie and reestablish, reenact, and reconnect their shared trauma. Ellie emotionally knows that Lev and Abby are trauma bonded too, just as she and Joel were, because Lev had been a part of their collective enmity since Abby brought him to fight Ellie and her group (Lev arrowed Tommy’s knee). What’s more, because Abby has Lev, Ellie knows that letting her go with her mind changed has even greater potential to redeem Joel as well. She knows that Abby will do anything to protect Lev, just as Joel did anything to protect her, and this relationship can help keep the legacy of Joel’s goodness alive.

Ellie’s continued will to get to Abby, to be lodged in her memories like a ghost herself, is predicated on making Abby question how Joel could've been wholly evil if he inspired the kind of singular, individualized determination Ellie exhibits over such a long time. So even though Ellie gives in to her desire to harm Abby as a way to make her change her mind about Joel, the fight sequence between the two of them never once shows Ellie trying to use her knife lethally; she slashes at Abby a lot, she tries to stab her in the face away from her neck veins (which is where she stabs most enemies she sneaks up on in the game), and when she does successfully stab her, it is only in her right shoulder, away from her heart. Ellie is reenacting the slow, torturous death Abby gave to Joel, and wants her to have scars that hauntingly remind her of their fight. But once again: she can’t kill Abby or else she will only be exactly like Abby, which won’t redeem Joel. And so when Ellie gets close to drowning Abby, this is when she flashes back to her final conversation with Joel, finally convinced: She won't ever forget who I believe Joel was. She’s convinced that’s what both these women feel assured the other is thinking after they go their separate ways. Ellie’s convinced that the good she thinks (or she must think) that Joel did will not be forgotten by Abby, even if she never got to experience it firsthand.

The last frame of the game is of an open window in Ellie’s former home. This indicates that Ellie has an opportunity, a window, to heal and become her own person. Before this, when she arrives at the farmhouse, Dina and JJ have gone. Ellie finds the guitar Joel gave her in her art studio. On top of the guitar case is a record Dina and Ellie danced to before she had the flashback in the barn. Ellie tosses this aside; she is still mostly focused on Joel. She is wearing a green flannel shirt that looks like the one Joel wore at the start of the first game. She tries to pick out the tune to “Future Days,” but can’t do so smoothly or as harmoniously, what with halves of her ring and pinky fingers missing. She stares out the window. And then we get the full flashback of her and Joel she’d started remembering in her final confrontation with Abby. We learn that Joel does not regret his actions in the hospital, saying he would do it all over again to save Ellie if “the Lord somehow gave [him] a second chance.” We see Ellie tell Joel she’d like to try to forgive him, even though she doesn’t think she can. She feels more assured, as she remembers this scene again, that she isn’t a complete monster—and that neither is Joel, who’d choked up and told her he’d like her to try to forgive him. Then she puts the guitar on the windowsill, unable to fully fulfill the promise she made to JJ to teach him to play when he’s older, but also unable to fully connect with Joel through one of the objects his ghost most intensely haunts. Now that Abby has to remember who rescued her, who let her go free despite the traumatic bond they share, Ellie can start to truly ease her grief from Joel’s loss, having been assured that his and her lives are now made more fully understood in all their moral complexity by Abby.

Ellie leaves the frame. As the camera lingers on the open window, we see Ellie walking across the field, away from the empty house. In the genre of ghost stories, homes are the places where we are most haunted. They hold the objects that connect us to our past and are themselves such objects. When Ellie leaves the abandoned home where she’s made memories with her loved ones Dina and JJ, she can either face or run away from the realization that, having pursued Abby at Dina’s disapproval, she now has not only been haunted but has been doing haunting of her own—causing grief to both enemies like Abby and her loved ones, just as Joel did.

With the painful reminder of her missing fingertips, Ellie will be haunted more consistently, more presently, by Abby instead of Joel. Abby has severed part of her connection with Joel’s ghost. Ellie’s body is now more like her own haunted house. She’s alone, as she’s feared. As she walks away from the farmhouse, Ellie has become more like Joel, in possibly more bad than good ways, to ensure his memory is redeemed. Yet she also faces a future where she can be better by learning to be her own person. And Abby is just as responsible as Joel is for both outcomes.

The Cycle of Grief Never Ends

Yes, a cycle of violence may end. But the cycle of grief, the one all humans experience through their loved ones’ deaths, does not. Humans cannot escape grief the way they can escape violence. Grief can only get more tolerable and less haunting. This tolerability is far more difficult to achieve, though, in the world of The Last of Us, where the infected populate the world like ghost-like beings themselves. And since mental/emotional ghosts don’t ever have to go away—ghosts being synonymous with the irrational—people in this world may feel even more tempted to use the everyday violence necessary to survive as instead a way to cope with being haunted by what they’ve lost, what they’ve never had, or what they wish had never been. By the time Ellie redeems Joel’s memory, she is more like Joel than ever before, an irrationally derived mix of both good and bad, as prone to using violence to solve problems as she is to using mercy. Though the cost is horrible, understanding that she herself has this mix is key to putting Joel’s ghost to rest. If she can understand the lengths Joel went to save her compared with the lengths she went to redeem his memory, she can be at peace with his ghost instead of being haunted by it.

Some might say my argument (or the game itself) presents an overly negative view of Ellie compared to Abby, who was merciful to Ellie twice before receiving mercy back and who lost more people in the conflict. But just as it is wrong for Abby to kill Joel in revenge, it is clearly wrong for Ellie to kill people just to make Abby remember her loved one in a better light. This is not justice either, and through her damaged hand, her reminder of Abby, Ellie will be haunted by the victims of the Joel-like, unnecessary violence she ended up doing to accomplish her goal. She is retraumatized by giving in to the emotional expediency of reenacting Joel's death by behaving like him. Right before she killed Owen and Mel, she was using an interrogation technique Joel taught her. She tortured Nora to get information before killing her just as Joel might’ve. And in her journey, she kills a varying amount of WLF soldiers, Seraphites, and the slavers who captured Abby and Lev, depending on the player’s style of play (one person loosely documented a playthrough where he found it’s tough but possible to kill less than ten people as a player controlling Ellie, excluding cutscenes).

One person Ellie kills no matter what, in a cutscene, is the so-called portable game girl, Whitney. She has nothing to do with Abby’s group besides being a fellow WLF soldier. Arguably she is the most innocent NPC Ellie kills that the player cannot avoid. She's playing a violent video game called Hotline Miami on a handheld PlayStation Vita device, and doesn't hear Ellie creep up on her. She holds a knife to her throat and asks for Nora’s location; when she gets it, Ellie pulls her knife away a bit and looks around the room, at which point Whitney tries to knife Ellie, only to be stabbed in the throat. “Fuck. That was dumb,” Ellie says afterward, speaking a description of both characters’ actions, but also saying this as a way to cope with and justify the moment. Like with Abby’s friends, she was giving Whitney a chance to live if she'd only provided information. I’d argue her looking off was her trying to find a way to tie Whitney up or stash her somewhere so guards wouldn't be alerted. This interaction stands out, though, and I've left it out of the earlier discussion about Ellie killing Abby's friends for a reason.

When the game was released there was a lot of discussion about “ludonarrative dissonance” in it. This refers to a notion that it is jarring when gameplay is thematically at odds with the narrative. Many argue it makes no sense for Ellie to kill indiscriminately when that's what Joel was both a victim of and perpetrated himself. But Whitney’s death, through the portable game system, carries a hauntological symbolization of how ludonarrative dissonance is a feature of the gameplay. The struggle the characters have with accepting deaths of the past is transferred onto players, making more real to them the dissonance the characters must experience to survive, despite surely not desiring, rationally, to kill others (save for Abby’s murder of Joel, which is harmonious with the character’s stated desire, though players generally find this death unjustifiable, largely because any premeditated murder strikes one as an action at the extreme end of irrationality). The game's robust stealth mechanics allow you to evade most human threats, to give the characters outside of cutscenes a chance to live, just as Ellie gives Abby's friends a chance. These mechanics even allow you to listen for and locate an NPC threat in a way that highlights their bodies into a featureless white shape—like that of a ghost’s. This constant image of a ghostly shape reminds the player that, the more NPCs are killed, the more haunted the protagonists will be in the long run, as the stakes to put their own loved ones’ ghosts to rest grow in proportion with every death. These stakes are reinforced by the fact that the NPCs often call each other by name, especially when they find one of their friends’ dead bodies. That Whitney is playing a game known to be violent (often the player must kill almost everyone in a Hotline Miami level to succeed) is a nod to the power players have to make Ellie and Abby reenact traumatic violence more by treating the game as “just a game” and not also a mechanism for self-reflection—a mirror. The game’s story is that Ellie and Abby's haunting grief drives them to reenact trauma so to create different outcomes: Abby feels her Dad was killed without justification, so Abby kills with a strong sense of justice; Joel wasn’t given a chance to live, so Ellie gives others a chance). However, the gameplay creates a plot that slightly varies as to how much the players let the characters give into the characters’ trauma responses. But make no mistake: the major story beats don’t work if Ellie doesn’t kill people in her quest to redeem Joel and if Abby isn’t forced to kill in her quest to redeem herself. All along, the game asks players to justify their actions with the reasoning Ellie and Abby both use as they stay stuck in trauma responses, which is that a certain amount of deaths, like Whitney’s, will be unavoidable due to the actions of others—the cycle of violence is their excuse. But players can understand that the haunted minds of both characters are trying to expel their grief by perpetuating the existing violence. If the characters think violence will cathartically put their loved one’s ghost to rest, they need an excuse to do it. One person’s justice is another’s needless violence.

So, as irrational and circular as it is, Ellie's killing is only committed to ensure that Abby wouldn't ever shake off the idea of Joel as a person good enough that he was worth killing people over, just as Joel thought Ellie was worth killing over. Is this wrong? Yes. Clearly. But what motivates this line of action is what the player is meant to contemplate: the limits of what humans will do for emotional well-being. These limits are as nearly horrific, unimaginable, and irrational as ghosts themselves, the game seems to say.

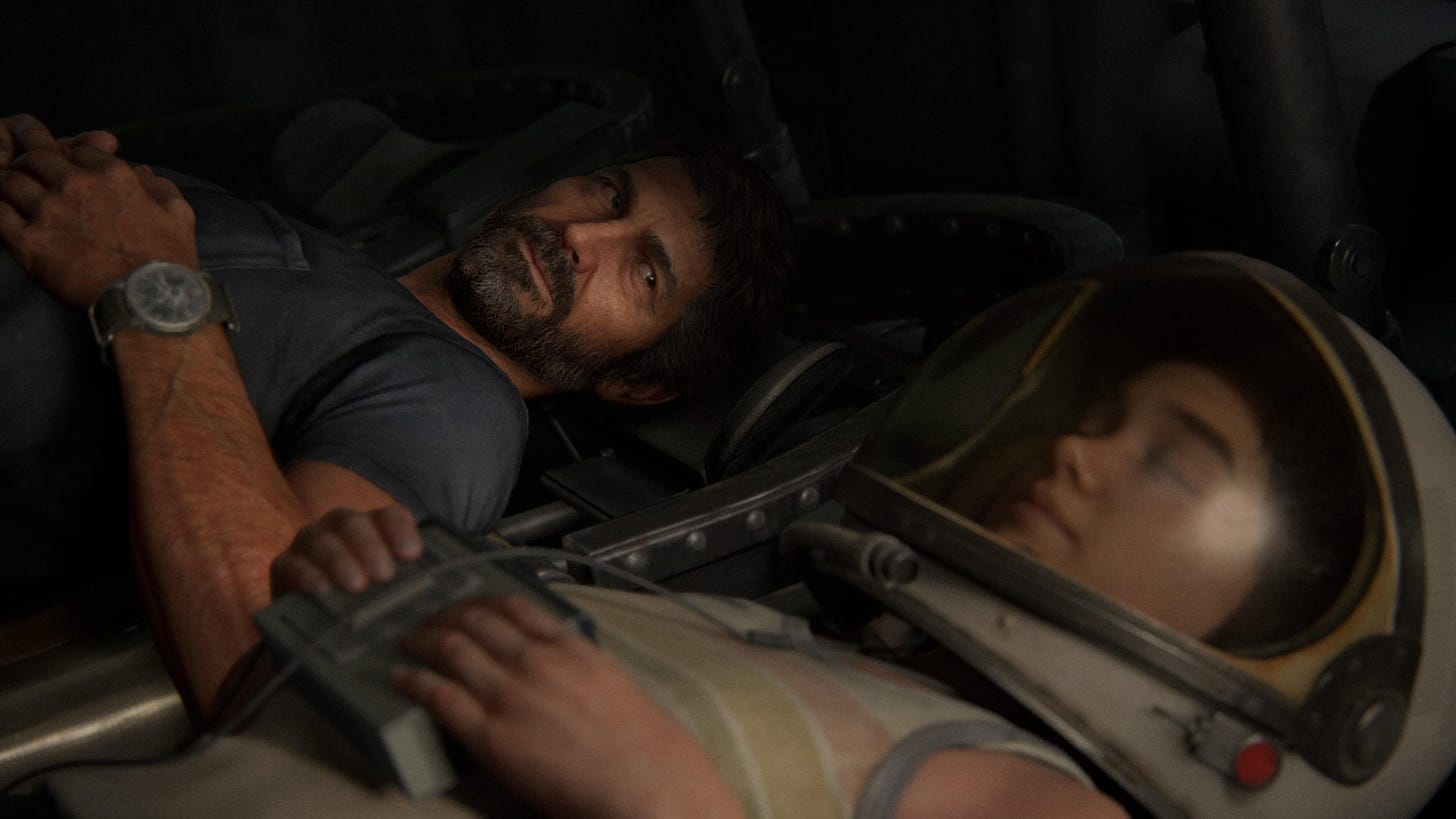

Ellie is only haunted by Joel more as her coping actions retraumatize her. And as reprehensible as it is, Ellie ultimately kills not for justice or redemption itself, but as collateral damage in her effort to preserve (or, as the game goes on, regain) her own sense of goodness, which I argue she felt she’d helped return to Joel in the first game. He’d become a hardened smuggler and killed many people to survive in the post-apocalyptic world that had taken the life of his daughter, Sarah. She was also killed irrationally. She was shot at the outset of the outbreak by a soldier following orders to kill anyone who looked like a possible threat—a ghost of a threat. Ellie gets Joel to open up about Sarah eventually as they get closer throughout the first game’s story, and this, combined with other details like Ellie’s love of superhero comics and the dumb fun of puns, indicates that Ellie identifies with bringing hope and comfort to others’ lives. As such, Abby's attack on Joel, a person she thought she made better, meant she could not grieve him and maintain her identity without preserving the memory of him as a good person—as the kind of person Ellie wanted to help others be like. Though it might be irrational in our moral universe, the fact that Joel only reverted to selfish violence to save Ellie from being sacrificed is not enough evidence for her to think of him as fully evil. They were trauma-bonded, yes, and Joel did hurt her a lot through this aspect of their relationship, but it’s hard to deny he also deeply cared about her well-being based on his behavior in both parts, especially in par two’s flashbacks. For example, he spends a lot of time finding a recording of the Apollo 11 rocket launch for Ellie, knowing she’s a fan of space and astronauts. When you love someone, you want to remember them fondly when you grieve them because this keeps the reality of their love alive; remembering them as only evil will make you question why you ever loved them back—and no one wants to believe their foundations of love are unhealthy or harmful. Grief skews our views of people so our love of them can persist—not really for their memory, but for our own. Ellie's redemption of Joel's memory is, in this way, really about letting herself move forward with whatever goodness she can carry on from her relationship with him. Once he dies, his ghost is just a creation of Ellie’s grieving mind, made to help her change her understanding of her memories of the past in ways she can live with. Abby’s creation of her father’s ghost was for the same purpose. Unfortunately, trauma keeps our brains from processing memories in completely rational, healthy, and healing ways. And then we find ghosts haunting the physical world around us, telling us we haven’t handled our grief.

We, the Players, are Haunted Too

The ghostly persistence of love motivates both Ellie and Abby. But without trauma, their hauntings may not have driven them to violence.

Consider that Ellie never does learn that Abby’s father was who Joel killed to stop her brain surgery. She only knows that the Fireflies believed there was one person, killed by Joel, who could’ve developed a cure because of a recording she finds. If she had known the doctor was Abby’s father Jerry, perhaps the violence beyond Joel's death never would’ve happened. Ellie might’ve rationalized that someone from Joel’s past was bound to seek retribution for what he’d done. But if Abby had told Ellie that Joel killed her father while Ellie was forced to watch her own father figure get beaten to death, would a later recognition of their shared traumatic grief have kept Ellie from killing Abby’s friends and others? Maybe, but her grief would’ve persisted, nonetheless, and it might’ve driven Ellie to an even darker place, a suicidal place, if she believed that Abby was somewhat justified when the impact of Joel’s death settled in. Ellie’s view of him would’ve become even more negative than it already had over the few years in the flashback scenes scattered throughout the game, when she finds out his lies. Even though fewer people probably would’ve died, Ellie might’ve felt she was more directly responsible for Joel’s actions if she’d learned of Abby's father and this could’ve made her take her life, precluding a possible future where she contributes to a vaccine. Ellie’s ignorance of Abby’s identity and her connection to the vaccine, while in the violent throes of trying to reclaim her own identity, might’ve kept her relatively sane amidst her grief. If she hadn’t been ignorant of who Jerry was, who would she have to blame for Abby’s hatred of Joel but herself? She was the one who trusted him to do the right thing for the sake of the vaccine. She was the one who’d tried to make him a good person again.

In another scenario, if Joel had learned who Abby was and why she wanted to kill him, he might’ve even let her kill him so long as he could get assurance that Ellie would be safe. Maybe the violence could’ve ended earlier than it did here, too, or at least manifested in less destructive ways. But again, the cycle of grief would’ve persisted, for both Abby and Ellie.

These possibilities and others haunt me when I think over the moral tapestry of the characters and world of The Last of Us. The protagonists haunt us because we see what happened and what easily could have. And sometimes we want to defend the ghostly vision of whichever narrative, real or unreal, haunts us most. First campers focus on what actually happened in the narrative, like Ellie, and struggle to be at peace with the choices the game creators took (like myself here) by understanding that past trauma causes irrational coping behavior. Second campers focus on a possibility that didn’t happen, like Abby, and they attack the game for its choice not to do X, Y, or Z, exerting revenge for a lack of what they hoped would happen (mostly Joel’s full redemption / focusing on an Ellie and Joel adventure again). Interestingly, the second campers might think they are behaving like Ellie since they see her quest as justified—they often defend Joel vigorously—but actually, they truly behave more like Abby, who brutally cuts down what takes away the emotions she wanted to have, without trying to understand why she didn’t get to have those feelings. This partially explains why second campers think the story fails if Ellie doesn't kill Abby and make her pay for not believing in Joel’s goodness, as they do. And on the flip side, first campers might think they are like Abby in seeing things as morally gray in their emotional processing of the story, but by too tidily dismissing Ellie’s choices as part of a “cycle of violence,” or even as a way for her to “forgive Joel,” they are behaving like Ellie by simplifying things for the sake of a morally superior view of a situation. First campers are prone to justifying anything the game does for the sake of some larger, cliched message, refusing valid criticism from second campers, like the game’s at times sputtering pace, the “it just so happens that these people in this chaotic world could find these others at super dramatic times” vibe of many of the story beats, or the often imbalanced allegory of a real cycle of violence between Israel and Palestine through the lens of the conflict between the WLF and Seraphites. The truth is that the game itself, like a ghost, operates on our memories emotionally, tempting us into irrational views of its story beats, just as the characters are tempted. With conscious effort, I have written this essay irrationally via my insistence on the hauntological lens. This seemed like the best way to analyze this particular piece of art, which does something that, regardless of its resonance with the theme of ghosts, is blatantly irrational in many ways: it not only makes you play as Abby, a seeming villain who murders the beloved character Joel, but it makes you play as her through the same three days you had just played as Ellie, to see her side of the conflict just as intimately.

Both camps are haunted by the game, they just react differently. But most players obviously can be more reflective than Ellie and Abby. Thankfully, we do not know the complex trauma of a post-apocalyptic world. There are war-torn and chaotic, nightmarish places in the world right now that we can understand a little better through this game’s characters and their pursuit of well-being (even if the game’s Israel-Palestine allegory isn't handled very delicately), but most players aren't going to hurt each other physically over the ending, no matter the ambient level of violence in their environment. And yet members of both camps have at times been emotionally violent, or worse, to those in or those that represent the other camp (Abby's voice actor Laura Bailey received death threats after the game was released). As irrational, harmful, and even criminal as these actions can be, they only belie the power of the emotions these characters evoke. It is a rare situation, and the gravity of this reality is why I’ve taken such pains to analyze the game. And maybe we all can be a little twitchy when defending our views, but we do not need to assume everyone is out to harm us personally just because they have a different opinion about a piece of art. For most people, narrative-focused games let us play out consequences for characters without experiencing few, if any, lasting ones for ourselves. They can help us put our ghosts to rest if we treat games as a therapeutic/cathartic/exorcising tool where we safely explore the possibilities of trauma and grief, rather than an arena in which to prove our superiority or status. But those who refuse this and instead use the game for violence are generally weaker and more selfish than either Abby or Ellie. They can learn and be better, however. Games are simulations; the people who play them are more complex than any character.

Though often at different scales of magnitude, we are all prone to being haunted by grief over the past or an unseen future. Both are things we lose. And often, as in the story and the player’s experience of The Last of Us Part II, the past we grieve is what takes away the future we thought we’d have. When we lose someone or something, the future is changed the more our beloved slips into the past—the more they become a fleeting image, a ghost in our minds. “When you're lost in the darkness, look for the light”—that is the motto of the Fireflies. If only the moral universe were that simple in the games, let alone in real life. Ghosts complicate our every choice. And they don't go away simply because we feel our choices are justified. Sometimes our ghosts are guiding us toward the light, the only light we think there ever will be.